Prologis warehouse, Chambersburg, PA

How do you stop an Exxon warehouse? It’s simple: Clinton Township citizens and neighbors who would be affected show up at the next council meeting, Wednesday, October 26 at 7:00 P.M. and tell their elected representatives on the council:

“Uphold our zoning! No amendments to permit warehouses!”

It seems that fast on the heels of our report on Thursday, Oct. 20, Exxon to bomb Clinton Township with 4 million SF warehouse, Exxon Mobil quickly decided to disclose what it has been quietly discussing for some time with Clinton Township officials. Exxon was reportedly going to announce this at a future council session: Letter from Exxon.

It’s now clear that Exxon is proposing a huge warehouse to be operated on Exxon’s long-time property by Prologis, which has massive warehouses strewn across New Jersey and other states.

Warehouses not permitted

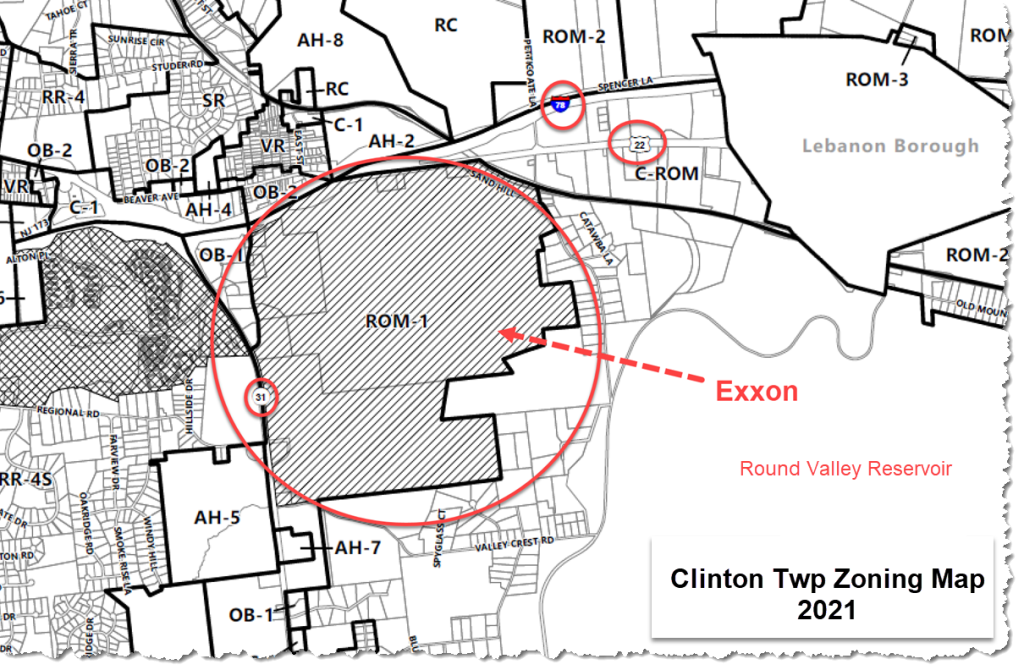

It’s not clear why the township would even entertain this proposal. The township’s ROM-1 zoning does not permit warehouses.

Here’s what Exxon wants, from its letter:

Exxon’s entire site is within the ROM-1 zone, or the Research, Office and Manufacturing district. This defines what a property owner may and may not do within a zone.

All Clinton Township has to do is say NO

In other words, the Clinton Township council can simply and politely tell Exxon NO, and do so on solid legal ground.

But Exxon is making a special request. Exxon is…

“…requesting that the Township Council consider amending the Property’s prevailing zoning to permit such a use.”

Why do we have zoning?

Zoning is the set of rules a community develops, under New Jersey’s Municipal Land Use Law (MLUL), to ensure the wishes of its residents are enforced. A town cannot implement arbitrary zoning — that would be illegal.

If the council agreed to “amend” the ROM-1 zoning to appease Exxon, what happens when other ROM-1 property owners ask for the same? Does the council upend the will of its residents on a case-by-case basis? Or, what is the law for? Will residents have to show up at public hearings in every single case after they’ve already enshrined a law that does not permit warehouses?”

Prologis would love that.

Without turning this into a detailed lesson in land use, a town’s governing body (often with advice from its planning board) legislates, or frames in its laws, what may and may not be built within its borders. Of course, these land-use rules must be consistent with State of New Jersey laws. Before zoning can be enacted through legislation by a town’s governing body, public notices are issued and the public (including developers and Exxon) are welcome to comment before a vote is taken by the council to enshrine the zoning into law.

Clinton Township’s restrictions on what can be built in the ROM-1 zone are defined by its community for the good of its community. These land-use laws are published and readily available to anyone considering building anything anywhere in the township.

Exxon wants to “make a deal”

This is how Exxon cues up a “friendly negotiation” with elected officials and with the planning board — when Clinton Township doesn’t need to negotiate anything.

Such imprudent “negotiations” are how Prologis builds fantastical structures that:

- introduce acres of impervious ground cover (rooftops and asphalt driveways and parking lots) that:

- impede groundwater recharge (that ‘s how aquifers refill residents’ wells)

- create storm water run-off (that pollutes streams and the water supply)

- generate thousands of diesel truck trips per day

- destroy air quality, and

- introduce massive amounts of traffic congestion and noise.

That’s why Exxon wants to cue up meetings — so it can make a deal.

Given that existing law already does not permit warehouses, it would be imprudent for Clinton Township to even consider wading into the murky legal swamp of “a negotiation.”

So why is the township even considering warehouses?

A developer has the right to appear before the township council and planning board and request a variance to legally depart in specific ways from the zoning. The planning board may approve a variance request if the applicant meets certain criteria, but it does not have to.

That’s why the township is even considering this, barring any inappropriate influence.

But in this case, Exxon does not even seem to be asking for a variance. Exxon is asking Clinton Township to consider entirely changing the zoning for the Exxon site.

“…amending the Property’s prevailing zoning to permit [warehouses].”

Exxon wants Clinton Township to change the law to suit Exxon, not the residents.

Why do we have zoning?

Towns have zoning to protect their residents. Residents elect officials to make the laws and to enforce them for the benefit and safety of the residents. These laws are made through an often cumbersome process: it takes a lot of work for a community to decide what’s best for all.

Clinton Township’s zoning is legal, it is clear, and it is what the residents decided they want for their community.

Warehouses are not permitted. In fairness and out of respect for a significant corporate resident, the council might nonetheless entertain Exxon’s presentation at a public meeting.

But the township’s position is already clear and enshrined in its laws.

How to Say It: “Warehouses are not permitted.”

That is all the township council and/or planning board needs to say to Exxon. The planning board isn’t even required to hear an application for a warehouse. (Why would busy, unpaid planning board volunteers waste their time, when they’ve already invested their time to make the township’s position on warehouses into law?)

The township’s only justification for NO needs to be nothing more than the very existence of its ROM-1 zoning.

Reprise: Exxon is looking for “a deal”

Could the council and planning board allow Exxon to build a warehouse anyway?

Yes, they could. They could “make a deal.”

For example, if Exxon can’t build a warehouse, it might threaten to build some extreme version of what the zoning does permit, and use the threat to get a deal whereby the township agrees to change its zoning to permit a warehouse.

Or, Exxon could point out (as it did in its letter) that a new warehouse could provide “a significant increase in real estate tax revenue.” But taxes on a warehouse are calculated not on what’s in the building, but on what the building is: a tin shell with relatively little value. The taxes would never compensate for the pains the warehouse would inflict on the township. This kind of deal is called “chasing ratables.”

Or, Exxon could offer to improve “prevailing traffic problems,” as it did in its letter. But the clever letter makes no mention of dealing with the future traffic problems that potentially thousands of truck trips per day would be generated by a 4 million square foot warehouse. (See ‘Warehouses in their backyards’: when Amazon expands, these communities pay the price.)

Or, Exxon could offer to improve “prevailing traffic problems,” as it did in its letter. But the clever letter makes no mention of dealing with the future traffic problems that potentially thousands of truck trips per day would be generated by a 4 million square foot warehouse. (See ‘Warehouses in their backyards’: when Amazon expands, these communities pay the price.)

In politics, these kinds of negotiations are referred to as “how sausage is made.” If you look, you’d never swallow what you see.

What will the council do?

It might seem clear what the township’s council should do — after all, it’s in the law!

But the council’s recent behavior with the New Jersey Water Supply Authority suggests council members are easily intimidated and overly impressed by seemingly powerful external forces. In the Route 629 case, council quickly bowed to a state agency that in fact has no power over the township or the county. Rather than say NO to permanent closing of a critical roadway, the council punted and said it wasn’t up to them to decide the fate of Route 629.

The council in fact had the power to say NO. When it failed to do so, the public rose up and had to do it for themselves.

What will the council do about enforcing and defending its zoning? It can work for and with its constituents, or it can replay Exxon’s song about why it’s a good idea to make a deal and allow a 4 million square foot warehouse.

Reprise: How do citizens of Clinton Township stop an Exxon warehouse?

Clinton Township residents and their mayor and council need to be clear, firm and resolute. Council can support the law and the community:

“Build under our zoning, or don’t build. Please go read our law. We’re under no obligation to defend our land-use laws or to negotiate warehouses. NO.”

An elected official’s obligation to their citizens is to apply the law. Not to make deals — or sausage.

An elected official’s obligation to their citizens is to apply the law. Not to make deals — or sausage.

The public’s prerogative is to expect and insist that its government use existing laws to protect the community.

What can citizens do? It’s simple: citizens show up at the next council meeting, Wednesday, October 26 at 7:00 P.M. and tell their elected representatives on the council: “Uphold our zoning! No sausage! No deals! No amendments to permit warehouses!”

HOWEVER: General Provision 165-93 provides that “Where a use is not specifically permitted in a zone district, it is prohibited.” So a warehouse in this case is both not permitted, and prohibited by exclusion.

: :